Studying tiny eyeless roundworms can help to shed light on the complex inner workings of larger animals, including humans.

“When we pose a question, sometimes it helps to start with a smaller system, rely on that experimental answer, and then apply that to mammals and humans,” said University of Michigan Assistant Research Scientist, Eleni Gourgou.

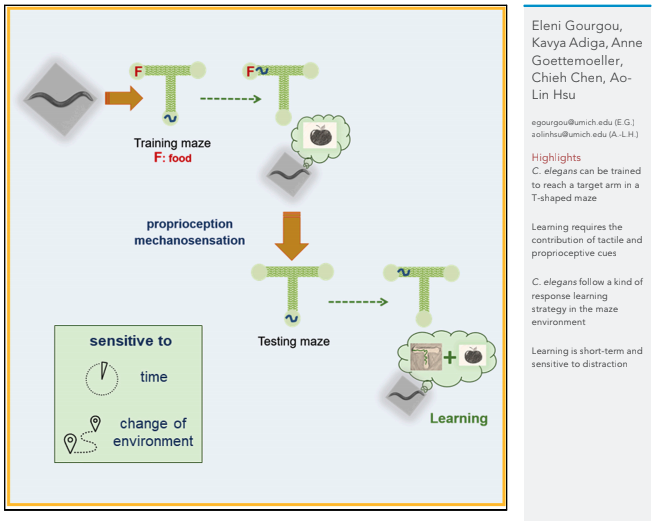

Recent research uncovered that nematodes (C. elegans) tiny eyeless roundworms with only ~300 neurons and less than 1000 cells, can learn to reach a target location in a simple T-maze after a single training session, during which they have successfully located food in baited training mazes. Researchers showed that learning nematodes rely on sensory input about the actions of their own body. Worms also use information about the interactions between their body and the structural elements of the maze, collected through touch sense.

The findings, published recently in iScience journal, are considered to provide a new paradigm and open a new research avenue, as until now it was not thought possible for such a small nervous system to be able to register and recall space-related information, especially in an eyeless creature.

research avenue, as until now it was not thought possible for such a small nervous system to be able to register and recall space-related information, especially in an eyeless creature.

C. elegans are a very successful model organism in experimental biology, and their learning abilities have been established and studied for quite some time, mainly in the context of chemical cues. Although there have been indications that C. elegans worms might be capable of some sort of spatial learning, until today this scenario remained unexplored, making Gourgou and Lin Allen Hsu, associate professor at the U-M School of Medicine, the first to thoroughly portray this new remarkable behavior.

The researchers showed that C. elegans nematodes learn to associate food with a combination of proprioceptive cues and information on the structure of the maze (floor/walls), perceived through mechanosensation. By using custom-made maze arenas, tailored to match the size of tiny (1mm long) nematodes, they demonstrate that C. elegans young adults can successfully locate food in T-shaped mazes and, following that experience, learn to reach a specific maze arm. C. elegans learning inside the maze prevails over conflicting environmental cues, and it resembles working memory, as it is sensitive to time and distraction. Researchers also show that the aging-driven decline of the maze learning ability observed in middle-aged animals can be reversed by controlled food deprivation.

“People have shown, using nematodes and mice, that reduced calorie intake can prolong both health and the lifespan,” said Gourgou. “Through some experiments, we’ve learned that controlled food deprivation can reverse the learning decline induced by aging. So, if we determine that food deprivation slows down aging, we need to figure out what the mechanism is there.”

As a next step, researchers are working to dissect the learning mechanism down to the single neuron level, figure out how aging affects nematodes’ spatial learning, and come up with interventions that can improve animals’ performance in the maze environment. They envision their findings as a road map to better understand how spatial learning works, both in small nervous systems as well as in more complex animals.

“This new information about the world around us allows us to have a better understanding of what nature and evolution is capable of,” said Gourgou.

Gourgou E*., Adiga K., Goettemoeller A., Chen C., Hsu A-L*.: “ Caenorhabditis elegans learning in a structured maze is a multisensory behavior”, *: co-corresponding authors. iScience, 24 (4) 102284, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102284, 2021. Link.

Selected as featured content (3 research articles from a total of 126), in iScience issue 24(4), 2021.