In a cluttered laboratory in the basement of the G.G. Brown building, ME Professor Noel Perkins and Dr. Kevin King are redefining the world of athletic training.

In a cluttered laboratory in the basement of the G.G. Brown building, ME Professor Noel Perkins and Dr. Kevin King are redefining the world of athletic training.

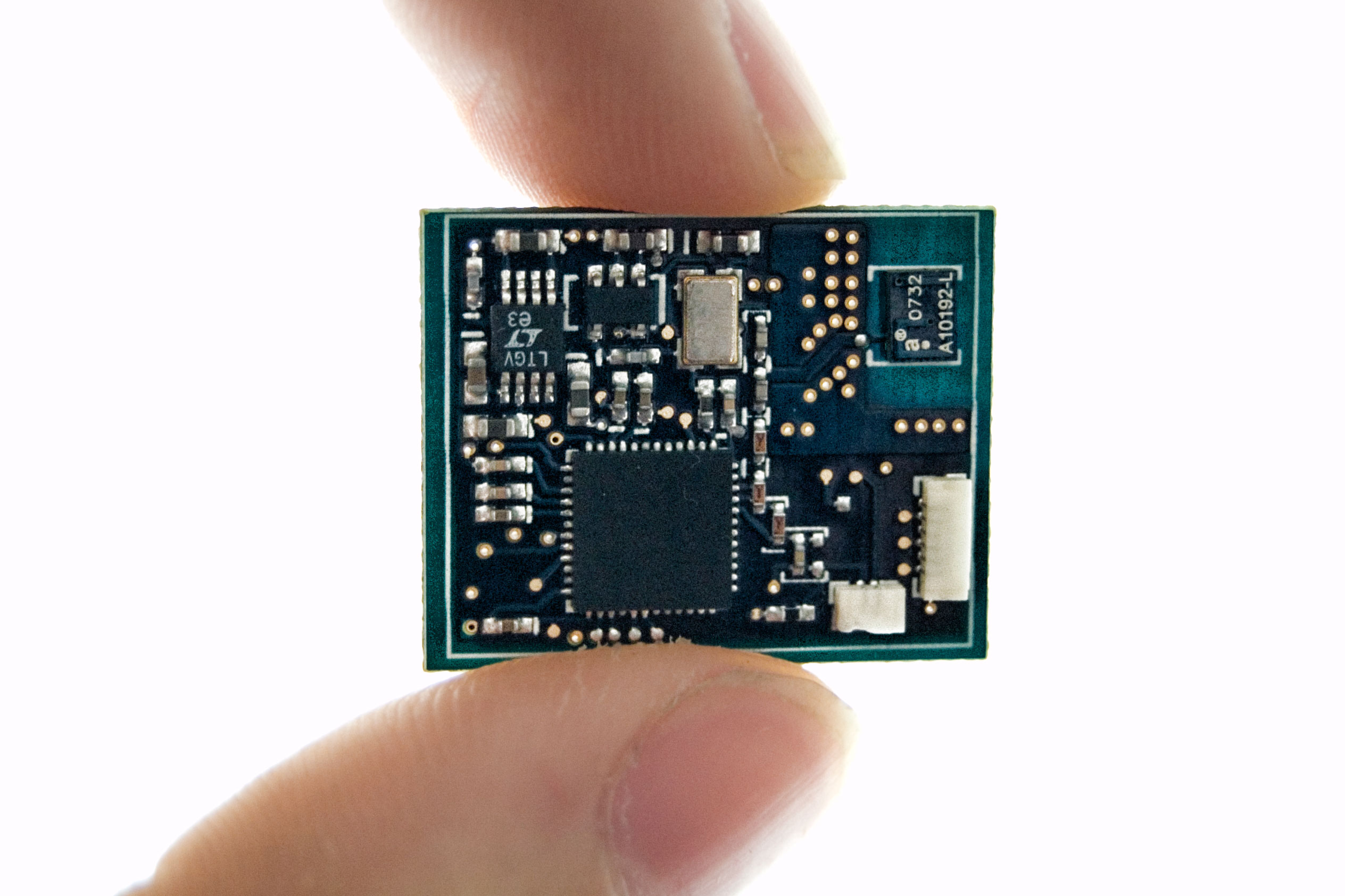

Every available surface of the lab lies buried beneath baseball bats, hockey sticks and bowling balls. A basketball rests in the corner, its insides exposed. What distinguishes this basketball from any other is the tiny chip—what is believed to be the world’s smallest wireless inertial measurement unit (IMU)—that Perkins and King have installed within. This invention impacts not only sports training, but extends into the fields of biomechanics, health monitoring, and surgeon training, as well.

An IMU measures the movement of a rigid body in space by computing its position and orientation (roll, pitch and yaw). Some examples of how IMUs are used include tracking aircraft, satellites and smart munitions. In 2000, Perkins began a project that would employ the principles of inertial navigation technology in a whole new realm of practical applications. The result of this project is a highly miniaturized wireless IMU that can be used in novel applications. “Our design provides wireless data transmission of six sensor outputs (three acceleration channels, three angular velocity channels) in a package about the size of a quarter,” Perkins said.

“Our research is really headed for the marketplace, which is unusual from UM’s perspective,” said Perkins. “Not every project [at the university] has a goal toward commercialization.” There are two patents for the use of the design in products that evaluate one’s athletic skill. The patented products so far on the market involve the sports of fly fishing and basketball.

“Our research is really headed for the marketplace, which is unusual from UM’s perspective,” said Perkins. “Not every project [at the university] has a goal toward commercialization.” There are two patents for the use of the design in products that evaluate one’s athletic skill. The patented products so far on the market involve the sports of fly fishing and basketball.

Perkins—a fly fishing enthusiast—was interested in creating a method to quantifiably measure the ability to fly cast, so he developed the fly cast analyzer using IMU technology. In 2005, Perkins commercialized the product and co-founded CastAnalysis, LLC. King, who received his doctorate degree from the University of Michigan, has been collaborating with Perkins on the project for the past seven years. He, too, is involved in a successful athletic training business using the small wireless IMU that he helped developed. His company, called 94Fifty, develops “sophisticated but cost-effective basketball skill analysis technologies for the mass market.” “It’s a wonderful blend of engineering with our hobbies, the things we like to do anyway,” said Perkins of his and King’s athletic training projects. “We’re lucky.”

The IMU as an invaluable teaching tool is being researched for a variety of other sports, such as golf, baseball, bowling and hockey. Once the chip is installed in, for example, a bowling ball, it transmits to a receiver connected to the athlete’s computer. A software program then displays information pertinent to the evaluation of the athlete’s skill. In the case of the bowling ball, a player can learn what axis the ball spun about and can learn how his or her average ball speed and RPM compare to those of the experts. But the invention’s potential is not restricted to improving one’s skills in competition. For example, in the health care industry, the miniature IMU can be used in exercise regiments, the detection of disease progression, and rehabilitation. “By knowing how the body moves, you can learn a lot about human motion including the learning of fine motor skills,” said Perkins.

The IMU as an invaluable teaching tool is being researched for a variety of other sports, such as golf, baseball, bowling and hockey. Once the chip is installed in, for example, a bowling ball, it transmits to a receiver connected to the athlete’s computer. A software program then displays information pertinent to the evaluation of the athlete’s skill. In the case of the bowling ball, a player can learn what axis the ball spun about and can learn how his or her average ball speed and RPM compare to those of the experts. But the invention’s potential is not restricted to improving one’s skills in competition. For example, in the health care industry, the miniature IMU can be used in exercise regiments, the detection of disease progression, and rehabilitation. “By knowing how the body moves, you can learn a lot about human motion including the learning of fine motor skills,” said Perkins.

The IMU has come a long way from the cumbersome, fist-size object tethered to an Ethernet cord that marked the project’s humble beginnings. However, the design is still far from finished. “Minimization is at a premium,” said King. King and Perkins hope to continue to shrink the IMU as more applications—such as a method of measuring how surgeons use tools to perform delicate surgical procedures—demand smaller and smaller technology.