It’s 6:45 AM, and you just finished a steaming cup of chai. The bottom hem of your kurti floats in the warm breeze. It’s already 26°C outside (80°F), and when you checked the weather report, it said it will get up to almost 40° today (104°F). You head back to your guest room to get changed before heading out into the countryside for a bike ride before work. On your 10 km loop, you pass by a local rice paddy, backdropped by banana trees, tall palms, and the rising sun.

You turn off the main road onto a gravel path, where you get passed by two motor bikes, a rickshaw, and a double decker bus. Green parrots zip in and out of nearby shrubs, and you hear the familiar sharp whistle of a kingfisher, a little bird characterized by the electric blue flash down its back. A farmer follows behind a small group of cows, while a sleepy toddler chases a puppy down the road. Just as the weather is getting steamy, you ride back through the familiar gates of your new workplace, Tamil Nadu’s leading neurorehabilitation center, the Poovanthi Institute of Rehabilitation and Elder Care.

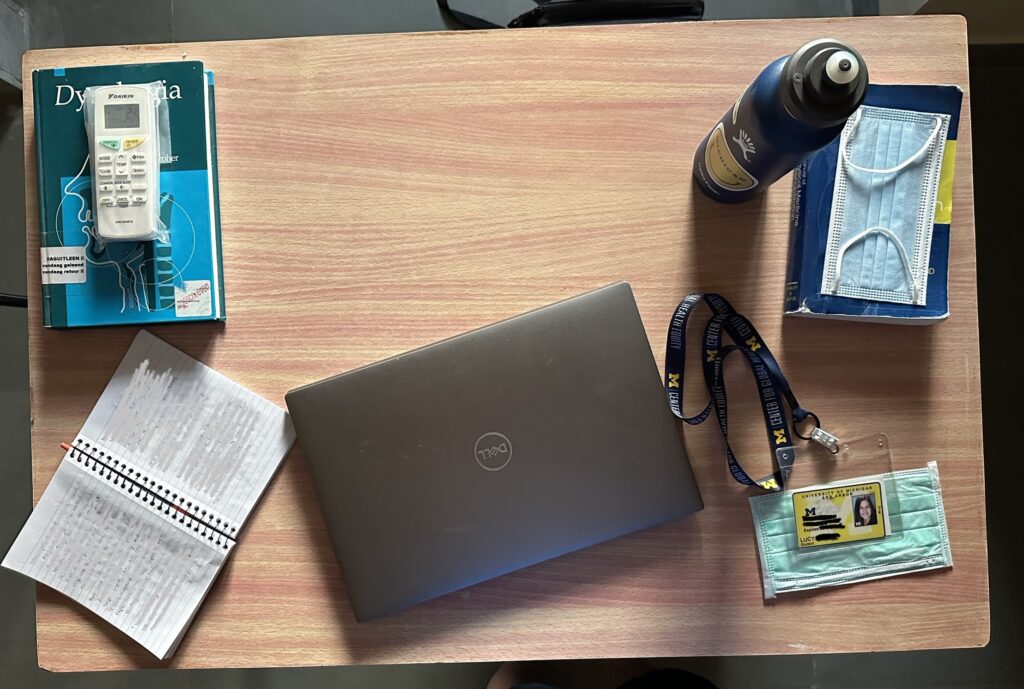

Hey there! My name is Lucy Spicher, and I am a PhD candidate in the Department of Mechanical Engineering. I am entering my third year as a graduate student researcher here at the University of Michigan. Believe it or not, most of my work days this summer started just like this one.

In early June, I traveled to Southern India with the Global Health Design Initiative (GHDI), a training program designed for students to define problems and develop and implement solutions to address essential healthcare challenges through collaboration with local stakeholders. It was my job to conduct a clinical needs assessment at a healthcare center for physical medicine and rehabilitation. Working together with an MBA student from the William Davidson Institute, our goal was to identify one-hundred unmet clinical needs, prioritize the top five, conduct a deep dive to understand the requirements and specifications of potential mechanical solutions, and to explore regulatory pathways for their local commercialization.

Here’s what a normal day looked like for us:

- 6:30 AM: Head to the canteen for morning chai*

- 6:45 AM: Bike ride, yoga, or time to catch up with family and friends in the US*

- 7:30 AM: Breakfast*

- 9:00 AM: Patient rounds with the Senior Doctor and Head Nurse

- 11:30 AM: More chai & follow-up conversations with the Senior Doctor

- 12:00 PM: Documentation and team debrief of observations from morning rounds

- 1:00 PM: Lunch

- 2:00 PM: Observation in the therapy halls, interviews with physical and occupational therapists, sketching / prototyping ideas, secondary research, etc.

- 4:00 PM: More documentation and team debrief time / check-in meetings with program advisors

- 7:00 PM: Dinner

*Events in constant conflict with my desire to sleep a little longer

Over the course of eight weeks, our team identified over eighty unmet clinical needs at the rehabilitation center. We worked closely with our local partners, drawing on their clinical expertise, to understand the number of patients affected by each need and the impact a potential solution could have on each patient. This information helped us prioritize our list of needs and identify the top five. At this point in the project, I conducted a deep dive to understand the requirements and specifications that a solution would need to meet for each of the top needs, while my business partner investigated regulatory pathways to commercialization in the local market for potential solutions.

Although we have since returned home to Michigan, our work isn’t over. We will continue working with our local partners in Tamil Nadu to develop potential solutions for each of the five projects we identified this summer. Supported by undergraduate student teams through the Mechanical Engineering Senior Capstone Design course and by our clinical mentors, we plan to generate concept ideas, prototype potential solutions, and conduct product testing throughout the Fall 2023 semester.

My academic career started through a similar program at Penn State (where I graduated with dual degrees in biomedical and mechanical engineering back in 2021) called the Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship (HESE) program, which provides students with opportunities to conduct field work in Sub-Saharan Africa, developing and supporting local business ventures. I discovered the program as a freshman, but I did not meet the prerequisites as it was intended for junior- and senior-level students. I reached out to the program director to see if I could support any of the student teams or their projects, which the director allowed, and so, throughout my time at Penn State, I worked as an undergraduate research assistant to support a Kenyan startup called Kijenzi.

At Kijenzi, our team worked to circumvent lengthy and expensive supply chains of medical devices by bringing the manufacturing facility to the source; we built a repository of medical device designs that were able to be 3D printed just a few miles from where the products were needed. I lived and worked in Kisumu, Kenya for a few months at a time over the course of two summers during undergrad, designing and 3D-printing splints, braces, and other tools to be used by local occupational therapists. Through HESE and Kijenzi, I took what I was learning in the classroom into the real world and made a real impact in people’s lives, but I still felt like I had so many questions and so much to learn. My curiosity and passion for research is what drove me to graduate school.

While reviewing literature as an undergraduate researcher, I discovered Dr. Kathleen Sienko’s work in design ethnography, which focuses on understanding the broader design context through user and stakeholder experiences to better inform design decisions. This investigation of context and its application to medical device design is exactly what I wanted to pursue throughout my PhD. I now work for the Sienko Research Group as a Graduate Student Research Assistant, spending my time investigating how experienced medical device designers discover and incorporate context during design decision making. In parallel, I get to use my training to improve my own design skills, by incorporating contextual information into the design of a wearable fetal monitoring system. The opportunities I’ve had to see the impact of engineering design in healthcare settings across the globe continues to inspire me as a researcher.

It’s now 4:45 PM. You’re finishing up your third cup of chai for the day. As you sit down at your desk to review your field notes from today’s observations, you note down the emerging themes in the data. You make a plan to meet with the head of occupational therapy tomorrow afternoon to clarify a few details. Tonight, they are serving chapati at the canteen (your favorite). You pack up your bag and head across the facility grounds to meet your new friends for dinner. In just a few weeks, you’ll return home to Michigan, but the partnerships you’ve developed will continue on, hopefully for many years to come.