Twisting spires, concentric rings, and gracefully bending petals are a few of the new three-dimensional shapes that University of Michigan engineers can make from carbon nanotubes using a new manufacturing process.

The process is called “capillary forming,” and it takes advantage of capillary action, the phenomenon at work when liquids seem to defy gravity and spontaneously travel up a drinking straw.

The new miniature shapes have the potential to harness the exceptional mechanical, thermal, electrical, and chemical properties of carbon nanotubes in a scalable fashion, said A. John Hart, an assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and in the School of Art & Design.

The 3D nanotube structures could enable countless new materials and microdevices, including probes that can interface with individual cells, novel microfluidic devices, and lightweight materials for aircraft and spacecraft.

A paper on the research is published in the October edition of Advanced Materials, and is featured on the cover.

The paper is called “Diverse 3D Microarchitectures Made by Capillary Forming of Carbon Nanotubes,” The lead authors are postdoctoral researcher Michael De Volder, and Sameh Tawfick, a doctoral candidate in Mechanical Engineering. Co-authors are doctoral students Sei Jin Park, Davor Copic, and Zhouzhou Zhou; and ME Associate Professor Wei Lu.

“It’s easy to make carbon nanotubes straight and vertical like buildings,” Hart said. “It hasn’t been possible to make them into more complex shapes. Assembling nanostructures into three-dimensional shapes is one of the major goals of nanotechnology and nanomanufacturing. The method of capillary forming could be applied to many types of nanotubes and nanowires, and its scalability is very attractive for manufacturing.”

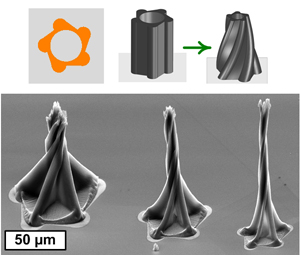

Hart’s method starts by patterning a thin metal film on a silicon wafer. This film is the iron catalyst that facilitates the growth of vertical carbon nanotube “forests” in patterned shapes. It’s a sort of template. Rather than pattern the catalyst into uniform shapes such as circles and squares, Hart’s team patterns a variety of unique shapes such as hollow circles, half circles, and circles with smaller ones cut from their centers. The shapes are arranged in different orientations and groupings, creating different templates for later forming the 3D structures using capillary action.

He uses a chemical vapor deposition process to grow the nanotubes in the prescribed patterns. Chemical vapor deposition involves heating the substrate with the catalyst pattern in a high temperature furnace containing a hydrocarbon gas mixture. The gas reacts over the catalyst, and the carbon from the gas is converted into nanotubes, which grow upward like grass.

Then he suspends the silicon wafer with its nanotubes over a beaker of a boiling acetone. He lets the acetone condense on the nanotubes, and then evaporate.

Credit: A. John Hart

As the liquid condenses, it travels upward into the spaces among the vertical nanotubes. Capillary action kicks in and transforms the vertical nanotubes into the intricate three-dimensional structures. For example, tall half-cylinders of nanotubes bend backwards to form a shape resembling a three-dimensional flower.

“We program the formation of 3D shapes with these 2D patterns,” Hart said. “We’ve discovered that the starting shape influences how the capillary forces manipulate the nanotubes in a very specific way. Some bend, others twist, and we can combine them any way we want.”

The capillary forming process allows the researchers to create large batches of 3D microstructures—all much smaller than a cubic millimeter, Hart said. In addition, the researchers show that their 3D structures are up to 10 times stiffer than typical polymers used in microfabrication. Thus, they can be used as molds for manufacturing of the same 3D shapes in other materials.

“We think this opens up the possibility to create custom nanostructured surfaces and materials with locally varying geometries and properties,” Hart said. “Before, we thought of materials as having the same properties everywhere, but with this new technique we can dream of designing the structure and properties of a material together.”

This research is funded by the University of Michigan College of Engineering and the U-M Department of Mechanical Engineering, the Belgium Fund for Scientific Research, and the National Science Foundation.

The university is pursuing patent protection for the intellectual property, and is seeking commercialization partners to help bring the technology to market.

Source and full article: Intricate, curving 3D nanostructures created using capillary action forces